Removing competition law from the English NHS – what can it mean?

Mary Guy

Lancaster Law School

The Queen’s Speech in October 2019 indicated the Conservative government’s intention to reform the competition provisions of the Health and Social Care Act 2012 (HSCA 2012) in order to facilitate development of integrated care models. This follows policy statements and legislative recommendations drafted by NHS England in connection with the NHS Long Term Plan in January and September 2019, which have been endorsed by the House of Commons Health and Social Care Committee.

These developments appear understood as “removing competition law” from the English NHS – apparently a popular move in view of the controversies surrounding the HSCA 2012, including criticism across the political spectrum and within and outside the medical profession. The HSCA 2012 competition reforms included extending Competition and Markets Authority (CMA) oversight of the English NHS, establishment of NHS Improvement as sectoral regulator (initially akin to OFGEM or OFCOM), applying general competition law and merger control, and the creation of an “NHS-specific” competition regime in the form of the “section 75 regulations” governing procurement, patient choice and competition.

However, “removing competition law” can have different meanings, with widely divergent consequences. At least three broad approaches can be identified and set out chronologically.

The first, the National Health Service (Amended Duties and Powers) Bill was introduced by the Labour MP Clive Efford in 2014, received 241 votes to 18 in favour of a second reading, but stalled in Committee debates and was discontinued by the calling of the 2015 election. This Bill sought partial exemption for the NHS from competition law by classifying it as a Service of General Economic Interest (SGEI).

The second, the National Health Service Bill, was initially introduced by the Green MP Caroline Lucas in 2015. This proposal sought to reinstate Secretary of State oversight and completely exempt the NHS from competition law. Although the proposal failed to gain sufficient support to continue, it has been re-tabled at different points by Labour MPs, and support for re-introduction was indicated prior to the 2019 general election.

The third is what is planned by the current Conservative government/NHS England, and developments in 2019 indicate what might be anticipated in forthcoming legislative proposals. In essence, the NHS Long Term Plan set out possible legislative change to remove CMA oversight from NHS mergers and NHS Improvement’s competition powers.

This paper considers how these three approaches differ, and how the current approach appears able to be misunderstood easily. Whereas the first two attempts to “remove competition law” from the NHS sought to address the underlying HSCA 2012 framework, thus remove, or reconfigure market structures, the current approach merely removes CMA oversight and the “NHS-specific” competition regime. This has raised concerns about “deregulation”, or paving the way for an unregulated market to operate at a time when private sector delivery may be expanding: in other words, it is not considered to “de-marketise” the NHS, which might be considered the aim of those opposed to “NHS privatisation”.

Joining up health and social care policy: implications for evidence identification from a rapid review of safeguarding

Anna Cantrell, Andrew Booth, Duncan Chambers

School of Health and Related Research (ScHARR), University of Sheffield

Background: The Health Services and Delivery Research (HS&DR) Sheffield Evidence Synthesis Centre produces reviews for the National Institute for Health Research HS&DR Programme that identify, evaluate and summarise the available research and highlight the implications for NHS decision-makers and priorities for further research. Previously the work programme has focused on health topics but a recent review on safeguarding of children and young people reflects a wider policy imperative to cover interventions delivered in health, social care or combined settings. Studies eligible for inclusion involved diverse health, allied health and social care professionals. The review team faced the challenge of ensuring that relevant research from social and health care was retrieved through database selection and other methods of evidence identification, as appropriate.

Method: The review aims to address the following research question:

What interventions are feasible/acceptable, effective and cost effective in:

-

improving health and social care practitioners' recognition of children or young people who are at risk of abuse?

-

improving recognition of co-occurring forms of abuse where relevant?

-

preventing abuse in these groups?

An initial search was conducted on MEDLINE and adapted to the following health databases: ASSIA, CINAHL (Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature), Cochrane Library, EMBASE, HMIC (Health Management Information Consortium), International Bibliography of the Social Sciences (IBSS), and PsycINFO. The wider remit required additional searches of Social Care Online, Social Policy and Practice, Social Services Abstracts, Social Work Abstracts, Social Science Citation Index and Sociological Abstracts.

The search was restricted to papers in English from 2004 to October 2019. Databases searched were selected to cover research involving social work, health care professionals and social care professionals. The search combined terms for child abuse or neglect with terms for safeguarding and child protection, early help and different health and social care professional roles. The search was combined with a reviews filter to find reviews and a UK filter to limit to research conducted in the UK.

Results: The searches retrieved 9990 unique references with 158 included to reflect the wider scope of the review. Included studies were categorised, using an a priori coding scheme, into strategies (multi-component system level), policy and guidance, organisational/cultural studies, initiatives (generally at the organisational level) and reviews (to include relevant international evidence). Expanding to cover social work and social care aspects increased the number of results retrieved dramatically impacting on the time taken to screen the references. However, the searches of Social Policy and Practice and Social Care Online, which covers grey literature sources, retrieved grey literature that would otherwise require even more time-consuming internet searches.

Implications: The safeguarding review is ongoing so that we are continuing to analyse the implications of this wider joined-up remit. However, barriers to inter-agency co-operation and ways of overcoming these featured in many included studies. With an increasing likelihood of rapid reviews spanning health and social care policy it is important to recalibrate existing sources and strategies for evidence identification. Future reviews could usefully analyse the implications of different databases, search methods and terminology, time taken and potential yield.

Disclaimer: This abstract presents independent research funded by the NIHR HS&DR programme under project number 16/47/17. The views and opinions expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the NHS, the NIHR, NETSCC, the HS&DR programme or the Department of Health.

How does implementation of a new national patient safety policy impact on patient safety priorities within NHS organisations? Lessons from Learning from Deaths

Mirza Lalani(1), Helen Hogan(2), Anamika Basu(2), Sarah Morgan(2)

(1)London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine, (2)London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine

Background: In 2017, guidance on how NHS providers learn from deaths in their organisation was implemented in acute and community/mental health trusts. In this study we aim to understand enablers and challenges to the implementation of the Learning from Deaths (LfD) policy and its impact on patient safety priorities within NHS organisations.

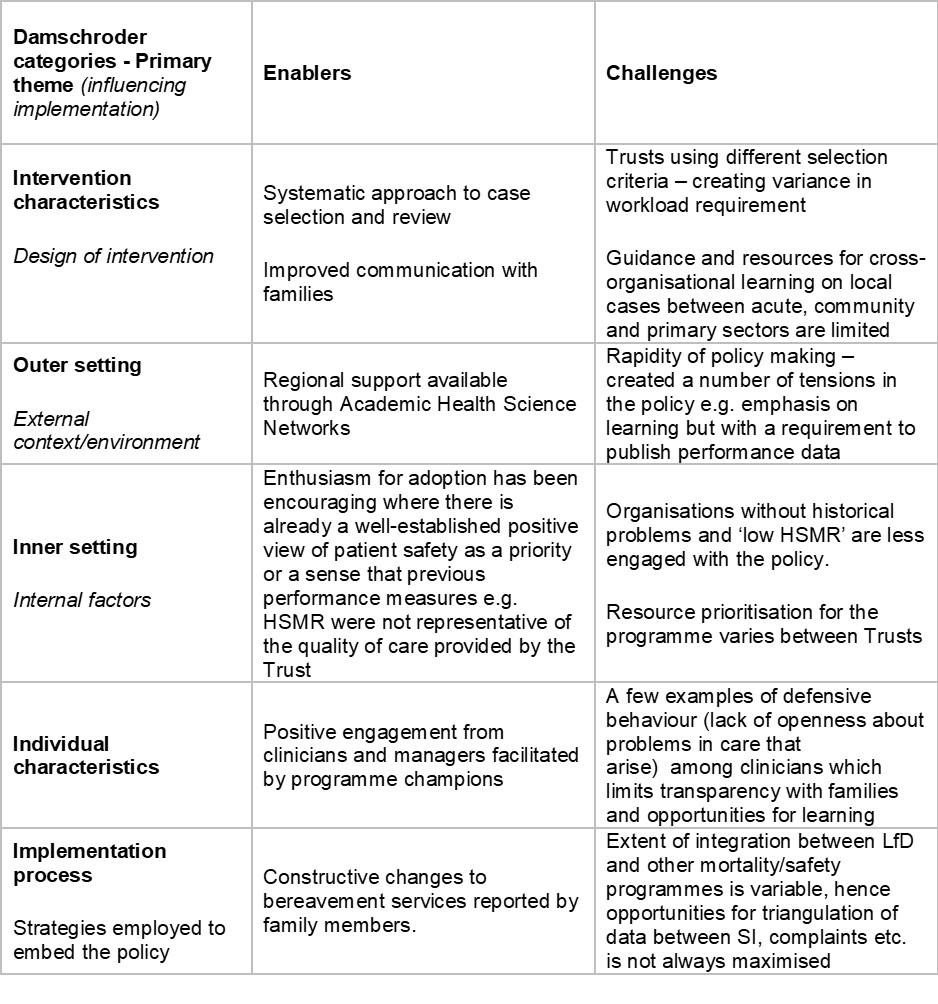

Method: This is a qualitative study using documentary analysis, observation of meetings and semi-structured interviews. Five NHS Trusts (3 acute, 2 community and mental health) were purposefully selected (late and early adopters of the policy) with 10-12 interviews per site. Interviews were undertaken at all levels of the organisations; senior and middle management, senior clinicians and frontline staff. Interviews (n=10) were also undertaken with policymakers from organisations involved in the design, implementation and assurance of LfD. A thematic framework analysis was undertaken using Damschroder’s Framework for Implementation Research.

Results: Policymakers outlined several intended outcomes of the policy. Firstly, they expected a shift towards a greater emphasis on examining deaths for learning rather than performance management. Secondly, the policy would provide a standardised approach to selection and review enhancing learning from a broader selection of cases, thus further minimising harm. Thirdly, they expected the policy to drive greater board accountability for patient safety through the requirement that a Non-Executive Director oversee the programme. Fourthly, an improved experience for family members with recognition that seeking feedback from bereaved relatives would improve the quality of care. Finally, that the policy may stimulate cross-organisational learning, given that examining care in this way would identify quality of care issues across the health and social care system. Using Damschroder’s framework, at the organisation level, preliminary findings have identified several enablers and challenges to meeting these patient safety priorities (see table below).

Conclusion: Overall, there has been recognition that Learning from Deaths has facilitated Trusts to take a more systematic approach to learning from clinical care. Acute Trusts feel the policy has fostered improvements in bereavement services and communication with families. Challenges to achieving patient safety priorities include practical barriers in terms of commitment and time to cross-sectoral learning from local cases, tensions between the dual purposes of the programme-learning and transparency and variable degree of alignment in information sharing between LfD and other patient safety programmes.

"This research is funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Policy Research Programme, conducted through the Quality, Safety and Outcomes Policy Research Unit, PR-PRU-1217-20702. The views expressed are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care."

Primary Care Networks in the English NHS: exploring policy construction, implementation, risks, and opportunities

Lynsey Warwick-Giles, Jonathan Hammond, Kath Checkland

The University of Manchester

Background: Over 99% (1,250+) of English general practices have now joined a Primary Care Network (PCNs). These new inter-organisational arrangements are framed nationally as foundational to the neighbourhood, place, system NHS scalar structure and a means through which many of the aspirations of NHS England’s Long Term Plan will be delivered. The mechanism to bring GP Practices together is a contractual one. The form of the contract is an ‘add on’ to the GMS/PMS/APMS contract, through a Directed Enhanced Service (DES). This is an optional contract; however there are clear incentives in place for practices to sign up to the DES, including additional monies for engagement and additional workforce roles. Within the first year of PCNs being in place, each PCN has had to come together, identify a Clinical Director and some form of governance structure across the practices within each PCN.

Method: We undertook 16 interviews with policy makers and stakeholders (07/2019-10/2019) exploring the in-depth objectives and intentions underlying policy changes in relation to PCN development. This was followed up by a national telephone survey of Clinical Commissioning Groups (CCGs) supporting PCN development locally (35 interviews covering 41 CCG areas (08/2019-12/2019)). Data was collected at a time when PCNs were trying to establish themselves and awaiting further guidance on what the expectations on them to deliver new service specifications would be.

Results: We show how PCN policy can be conceptualised as comprising three overarching thematic containers: Collaborative general practice; inter-organisational place-based care; support and (re)shape the system. These provide a frame within which we explore how both policy makers and those involved in the facilitation of PCN establishment and early operation across CCG areas understand a range of problems and risks facing PCNs both now and in the near future. We show how the breadth of policy aims creates space within which expectations of what PCNs will do and achieve can grow and vary between different groups of stakeholders, with associated risks from misunderstandings and poorly designed incentives. Data from the telephone survey suggests that there is an acceptance that GPs working together and with other organisations in a collaborative manner is the right thing to do, bringing potential benefits for patients, practices and the system. However, telephone respondents highlighted the complexities and challenges being faced locally including pre-existing collaborations being altered to ensure that local PCNs adhere to the PCN guidance, with some staff reporting that they feel they are being penalised for being ahead of the policy. Furthermore, CCGs are playing a pivotal role in supporting (through both time and resource), PCN development and are often referring to themselves as protecting the PCNs from becoming overloaded with system, place and neighbourhood demands.

Implications: There is an overall consensus that PCNs have potential and if successful they may bring about improved outcomes for the system, practices and patients. However, the policy aims of PCNs seem confused and the contractual nature of the PCNs, being general practice focused, will make collaboration with the wider system potentially more difficult. There are concerns at CCG level that the expectations that are being placed on PCNs through the currently proposed service specifications will mean that PCNs will become overwhelmed before they have even begun any of the work. In addition, the absence of detail about changes to the NHS standard contract means that there is a lack of clarity of how PCNs will work with community services which seems to underpin the delivery of these service specifications.